This week at Summers-Knoll, we had our first early release/half-day, professional learning session for teachers on Wednesday, October 9th. (Thank you to the aftercare staff who made it possible for homeroom teachers and specialists to engage in this learning together.) We used this time to take a deeper dive into our schoolwide, Climate Science initiative with the founder of Summers-Knoll school, Ruth Knoll.

Over the past two years, Ruth has been taking her own deep dive into the science of soil. As a dedicated student of the Soil Food Web School, founded by Dr. Elaine Ingham, Ruth has been studying the science of thermal (aka hot) composting.

From examining microbial life and fungi under a microscope to giving us a tour of various types of composts (e.g., Johnson-Su, Bokashi, Vermicompost) in various stages of development, we learned about the critical importance of compost in the broader scope of climate science as well as how to create thermal composts using a standardized formula of 10% high nitrogen, 30 % nitrogen, 60% carbon.

Prior to our field trip to Ruth’s house on Wednesday, we met virtually with a Soil Food Web consultant, Loida Vasquez, who works in the agricultural industry with farmers across the U.S., Mexico, Costa Rica, and Colombia.

Loida taught us about the different types of microbial life in a healthy, nutrient-rich compost, their functions, and their critical role in plant life and the life of our planet.

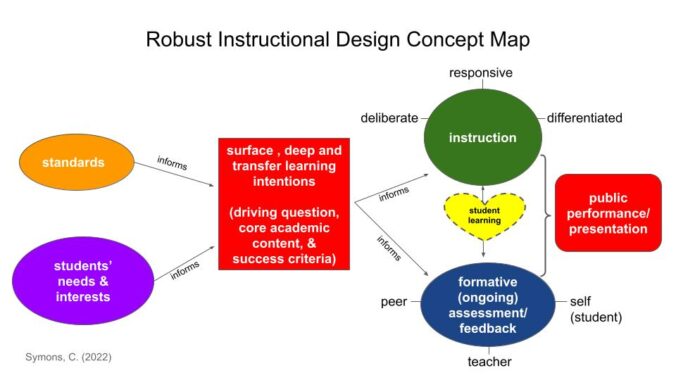

When teachers’ build their domain knowledge, they, in turn, can create more meaningful opportunities for student learning. Through translating domain knowledge into curriculum and instruction for students, teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge deepens. For example, if you wanted to better understand the dust bowl history of the U.S., one of the best ways to do so would be to teach someone else about it because to teach someone else about something, you need to have both the domain (aka content) knowledge as well as practical knowledge of how to create meaningful and engaging experiences through which students learn. As one of my yoga teachers, Baba Hari Dass said, “Teach to learn.”

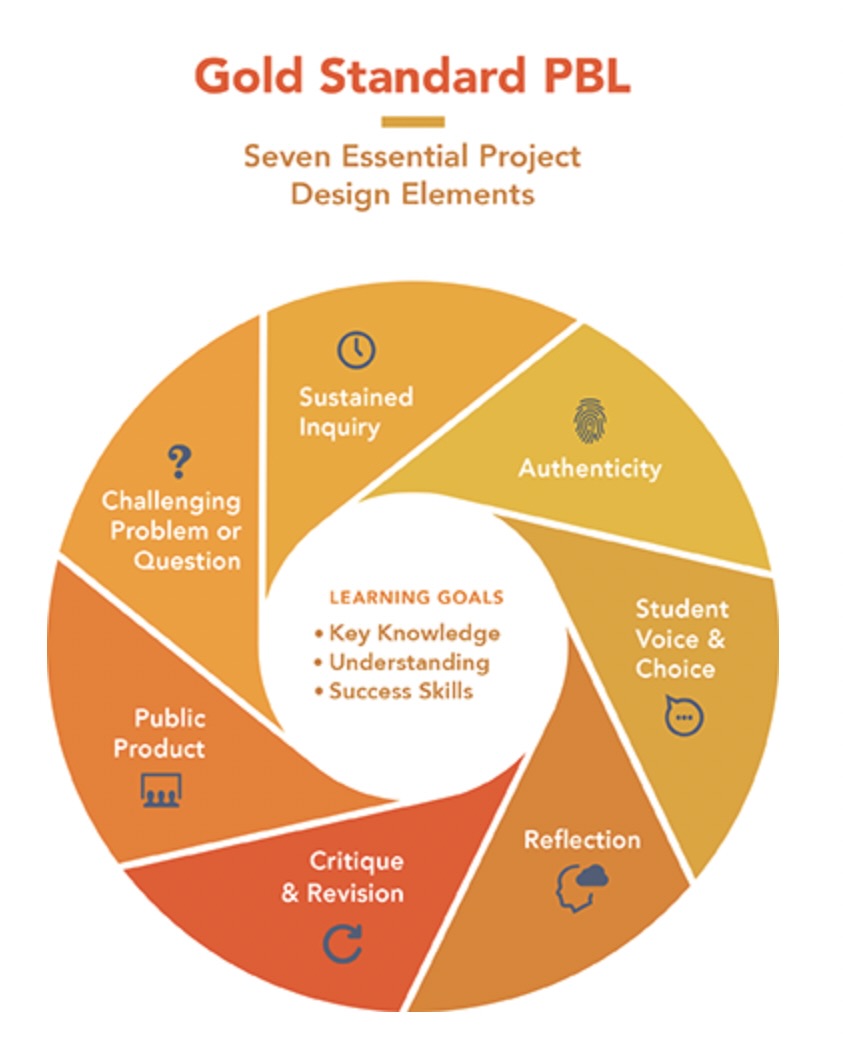

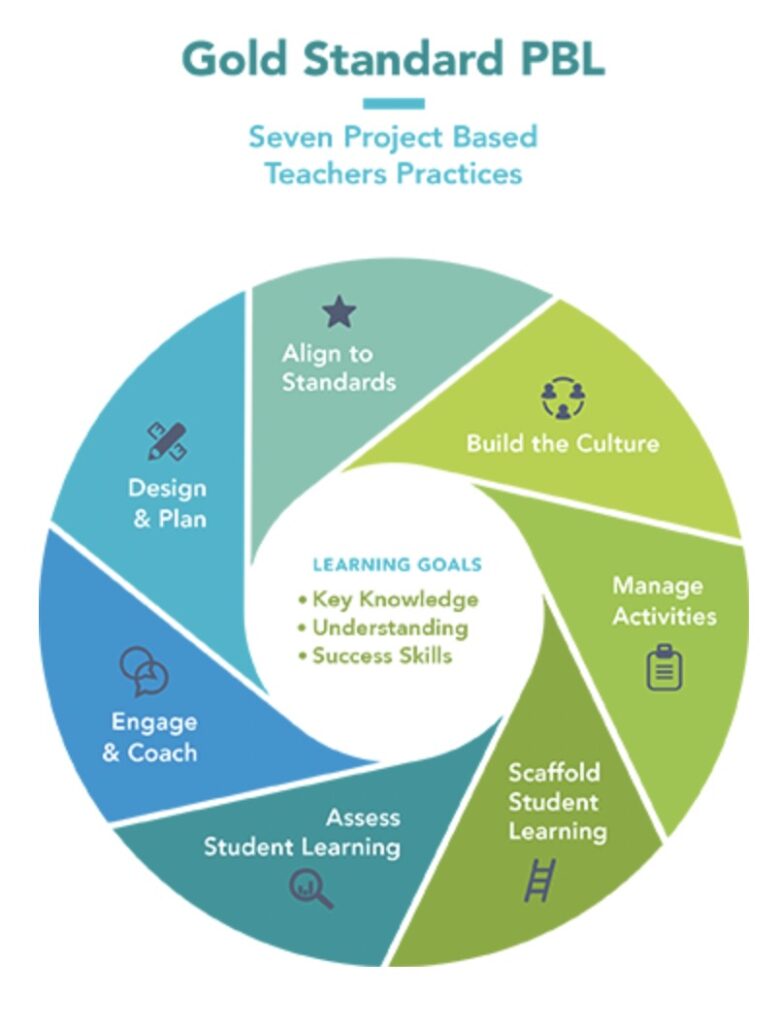

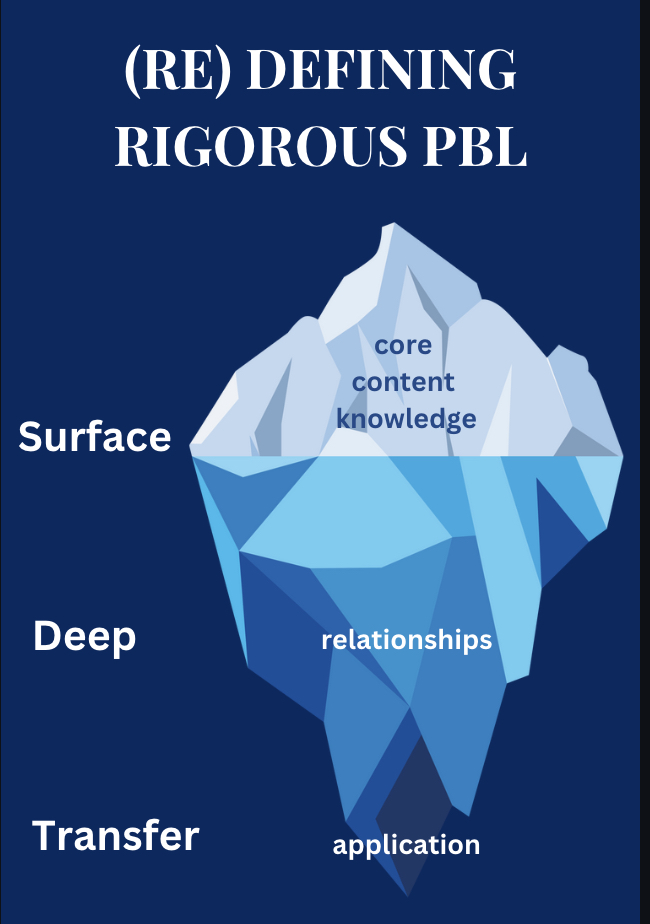

Thank you, Loida and Ruth, for partnering with us on this journey. At Summers-Knoll, we take project-based learning seriously. We recognize the importance of continually deepening our knowledge as educators in ways that align with how we want students to learn as well: surface, deep, and transfer. If a pedagogical approach, such as PBL, is going to foster transformative learning for students, teachers need to also have transformative learning opportunities.